Overview

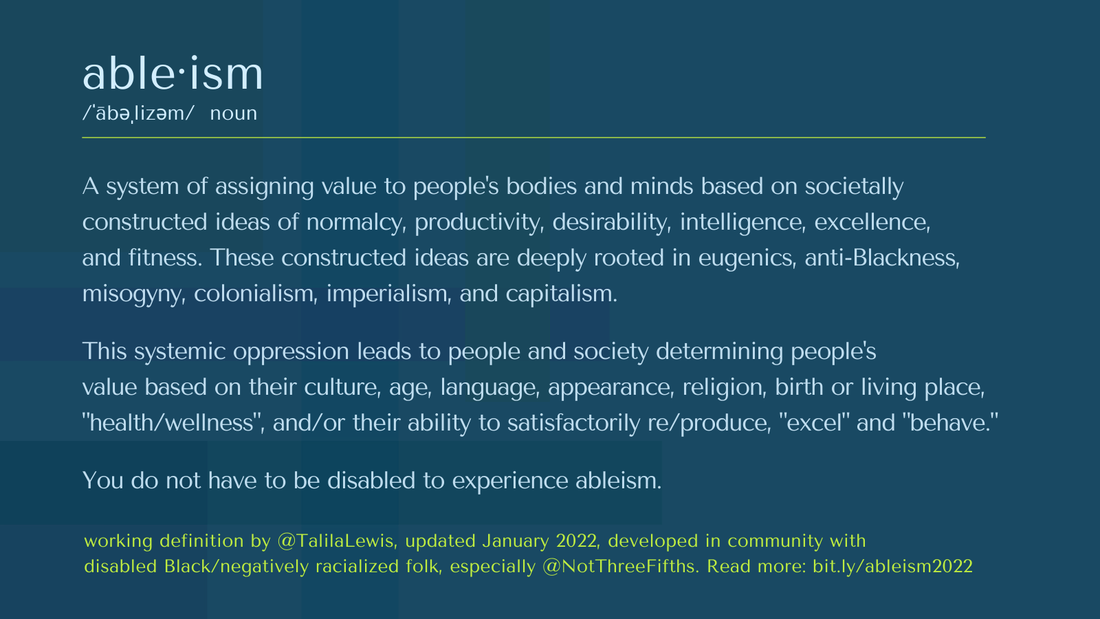

Ableism

There is an important distinction to make when considering ableism in an arts classroom. Many therapies are concerned with altering disabled and neurodiverse folks to fit into neurotypical and abelist societal structures and forms of communication (medical model). (More on Disability Models here).

Some art therapy approaches aim to provide students with access to communication methods that suit their needs and to support their self-expression (social model). Some art therapy approaches ascribe to deficit thinking about disabled and neurodiverse folks.

Disability arts communities are pushing further beyond the social model by troubling the ways in which disability’s relationship with the arts is always framed through art therapy. Sean Lee (curator of Tangled Art + Disability, the first and only disability led art gallery in North America, located in Toronto) suggests in this essay that “Art has also held a mainstream relationship to disability for its therapeutic good. Today, we mark disability as a good for art.” He invites us to question how flipping the script might allow us to explore the ways in which disability challenges what we conceive of as art.

We intend to share resources which embrace a disability justice orientation and to continue to engage in this work as an organization. We wish to challenge educators to question the orientation to addressing disability only through special education and to encourage them to avoid deficit thinking or the medical model which may cause harm, trauma, and further inequity.

A note on language: Some folx push back against person-first language (i.e. person with disability), choosing instead to use identify-first language (i.e. disabled person). Any language that connotes pity (e.g., "suffers from" instead of "has/is living with") is not appropriate. Mentions of someone's disability should occur only when relevant to the rest of the information communicated (e.g., not appropriate to include when discussing their favourite colour, but appropriate to include when discussing their access needs). For further recommendations, see the Linguistic Ableism article included in the General Education resources below. Further reading: Sinclair, J. (2013). Why I dislike “person first” Language.

General Education Resources

- Linguistic Ableism - Ableist words and terms to avoid

- Ontario Government's Inclusive Design Cards (Wonderful resource with prompts about designing with empathy for invisible disabilities, designing for inclusive physical experiences, designing for inclusive audio experiences, designing for inclusive visual experiences, and designing for inclusive thought experiences; downloadable PDF or Word document as well).

- Universal Design for Learning - CAST Guidelines

- UDL Tech Toolkit

- LEAD INCLUSION | Home | Lee Ann Jung - UDL

- Disability-Centred Movement: Supporting Inclusive Physical Education | Ophea.net

- Titchkosky, T., & Michalko, R. (2009). Introduction. In Rethinking normalcy: A disability studies reader (pp. 1–14). Canadian Scholars’ Press.

- Sins Invalid curriculum (Disability Justice Primer, etc.)

- Changing the Framework: Disability Justice by Mia Mingus

- Implementing a Disability Justice Framework: An Interview with Sarah Jama, Co-founder of the Disability Justice Network of Ontario

- Access Intimacy // Access Intimacy, Interdependence and Disability Justice // Moving Toward the Ugly: A politic beyond desirability by Mia Mingus

- Crip/Cripping Practice - Powerpoint presentation

- Critical Disability Theory

- Enabling Whom? Critical Disability Studies Now

- Cripping neoliberal futurity: Marking the elsewhere and elsewhen of desiring otherwise

- Madden, S., Leeds, S., & Carmichael, R. (Hosts). (2020, December 19). ‘I want us to dream a little bigger’: Noname and Mariame Kaba on art and abolition [Audio podcast transcript]. In Louder than a riot. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2020/12/19/948005131/i-want-us-to-dream-a-little-bigger-noname-and-mariame-kaba-on-art-and-abolition

- Crip Theory: Cultural Signs of Queerness and Disability

- A Guide to Sighted Allyhood

Performing Arts Resources

- Benwell, F. (2018). A Play in Many Parts. In M. Nijkamp (Ed.), Unbroken: 13 stories starring disabled teens (pp. 205–239). essay, Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Chandler, E. (2019). Introduction: Cripping the Arts in Canada. Canadian Journal of Disability Studies, 8(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.15353/cjds.v8i1.468

- Das, S. (2021, June 13). Tales from a disabled theatre school grad -. Intermission. https://www.intermissionmagazine.ca/artist-perspective/tales-from-a-disabled-theatre-school-grad/

- Disability Arts Online - UK-based organisation advancing disability arts and culture. Their website, which includes magazine articles, blogs, events, and a directory of artists.

- Eisenhauer, J. (2007). Just Looking and Staring Back: Challenging Ableism through Disability Performance Art. Studies in Art Education, 49(1), 7–22. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25475851

- Estaban, J. M. (2023). Crip Provocations for Dance. Provocations Journal 3. https://www.provocationsjournal.com/volume-3/touchstone-vol-3/crip-provocations

- Esteban, J. M. (2023). My panalangin of (un)belonging: Encountering still gestures of prayer, improvising still movements through depression. Disability Studies Quarterly, 43(1). https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v43i1.9655

- Garland Thomson, R. (2005). Dares to stares: Disabled women performance artists & the dynamics of staring. In C. Sandahl, & P. Auslander (Eds.), Bodies in commotion: Disability & performance (pp. 30-41). University of Michigan Press.

- Guide for making accessible theater subtitles

- Hadley, B. (2020). Allyship in disability arts: Roles, relationships, and practices. Research in Drama Education: The Journal of Applied Theatre and Performance, 25(2), 178-194.

-

Healey, D. (2021). Act iv: At home by myself with you. In Dramatizing blindness: Disability studies as critical creative narrative

(pp. 117-135). Palgrave Macmillan. - HowlRound

- Inclusion in the drama classroom: Assessing your space. Theatrefolk. (n.d.). https://www.theatrefolk.com/blog/inclusion-in-the-drama-classroom-assessing-your-space

- McCaffrey, T. (2018, August 4). Technology and disability performance: Our shifting perspectives. The Theatre Times. https://thetheatretimes.com/technology-and-disability-performance-our-shifting-perspectives/

- McGreevy, B. M. (2019, February 27). Cripping the arts. Toronto Metropolitan University. https://www.torontomu.ca/fcs-news-events/news/2019/02/cripping-the-arts/

- Olson, M. (2016). She begins to move. In Y. Nolan, & Knowles, R. (Eds.), Performing indigeneity (pp. 271-283). Playwrights Canada Press.

- Penketh, C. (2020). Towards a vital pedagogy: Learning from anti-ableist practice in art education. International Journal of Education Through Art, 16(1), 13–27. https://doi.org/10.1386/eta_00014_1

- Quillen, C. (2021, October 18). Are we advancing equity for students with disabilities? - arts education partnership. Arts Education Partnership. https://www.aep-arts.org/multimedia-resources/are-we-advancing-equity-for-students-with-disabilities/

- Rare Theatre (Toronto): Children Speak Radio Play

- Reason, M. (2018). Ways of watching: Five aesthetics of learning disability theatre. In B. Hadley & D. McDonald (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of disability arts, culture and media (pp. 163-175). Routledge.

- Resources to Create Equity in Dance and Theatre — Momentum Stage

- Roy, D. (2020). Drama, Masks, and Social Inclusion for Children with a Disability. Handbook of Social Inclusion: Research and Practices in Health and Social Sciences, 1-14.

- Sheppard, A. (2019). Staging bodies, performing ramps: Cultural, aesthetic disability technoscience. Catalyst, 5(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.28968/cftt.v5i1.30459

- Sills, N. (2020). Students with Physical Disabilities in High School Drama Education: Stories of Experience (thesis). Queen’s University, Kingston, ON. Retrieved October 15, 2023, from https://qspace.library.queensu.ca/items/0d9c7d8e-75b5-4eca-bbcc-75f18666a2c7.

- Virtual Theatre Toolkit - A Workbook for Educators, Facilitators and Performers with Disabilities

- Watkin, J. A. (2022). Sending care from afar: Pandemic postcards and disability dramaturgy. Theater, 52(2), 33-47. https://doi.org/10.1215/01610775-9662208

- Zdeblick, M. N. (2023). “Play my clip!”: Arts-Mediated Agency in disability-centered learning and research. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2023.2264243

- Playwrights Canada Press: Disability Theatre

https://brocku.ca/diversities-in-actor-training/ableism-and-diversities/

Community Practitioners

- CreativeConnecter.Art (Canada): Connecting you to Deaf and disability art, culture and community

- Dramaway

- The Disability Collective at Buddies in Bad Times Theatre

- Famous PEOPLE Players

- Abilities Arts Festival

- Common Boots Theatre

- Chisato Minamimura draws on improvisation, movement, and her unique way of exploring sound and movement as a Deaf artist.

- Picasso PRO

- Propeller Dance

- L'arche Toronto: Sol Express

- Bamboozle Theatre - UK with some international offerings

- Tobi Green-Adenowo - Founder of Disabled Power Network, Creative Director and TV Show Host, Disabled Queer Black Muslim, Wheelchair Dancer

San(e)ism

The system of oppression that impacts individuals who identify with madness is known as sanism (or saneism). Sanism manifests through societal stigma, discrimination, and negative stereotypes against those perceived to have mental health conditions or atypical psychological experiences. This oppression often results in marginalization, lack of access to appropriate healthcare, social exclusion, and the invalidation of their lived experiences.

Sanism (or saneism) manifests through constructions of madness in similar ways to disability. In the arts, representations of madness appear constantly in theatre and madness and dance have a long history of association.

The medical model treats madness as a form of illness, pathologizing psychological and emotional differences in ways that invalidate the experiences of folx who see their differences as part of their identity rather than as disorders. This approach also treats these psychological and emotional differences as something to be fixed, and historically, this "fixing" has involved forms of torture (e.g., electroconvulsive therapy, lobotomies, institutionalization/incarceration, forced medication, conversion therapy, isolation and restraint, over-medication).

The term "mental illness" can reduce complex human experiences to mere medical conditions, ignoring the social, cultural, and personal dimensions of these experiences. For example, "homosexuality" was once considered mental illness, and "mental illness". The recent focus of the medical model is addressing stigma by educating the general population about "mental health" or "mental hygiene" and making individuals responsible for their psychological and emotional experiences, portraying mad folx as unclean. Some folx use the term "mental health user" or "mental health survivor" to move away from the notion of brokenness or the idea that thoughts need to be fixed, to move away from the conception of themselves as a problem (deficit thinking).

While the social model turns the focus from pathologizing to a focus on immediate accessibility and rights, this approach may not address long-term sustainability and systemic change comprehensively. Addressing societal barriers is important, but it not sufficient, as it does not disrupt what is viewed as 'normal' and what is being 'included' (accommodated). The social model primarily addresses physical and environmental barriers but may not fully engage with emotional, psychological, and relational aspects of madness, sometimes downplaying the real, lived experiences of pain, fatigue, and other challenges of these identities. Recently, there is a shift from acknowledging "rights" to accommodating "needs" on an individual basis, related to neoliberal interests in reducing costs associated with making systems accessible.

Dr. Brenda LeFrancois - "Mad Studies: Maddening Social Work"

In contrast, the mad pride/disability justice framework highlights the importance of community support, collective care, and mutual aid within disabled communities. It acknowledges the need for medical support while seeking societal change, it disrupts what is considered "normal" or "sane" to create more space for a range of psychological and emotional experiences. This framework also creates space to recognize the ways that collective trauma contributes to the need for a greater range of emotional and psychological expressions. Consider the rise in "mental health crises" during the COVID-19 pandemic as an opportunity to recognize that combating stigma around "mental illness" is insufficient in supporting the range of psychological and emotional experiences of individuals.

The Mad movement offers alternative ways of naming elation and distress -- our different “habits” or “moods.” Some of us may use medical language to describe ourselves: mania, depression, obsession. But many others prefer different terms -- such as “extremes of consciousness,” “unusual beliefs” -- or no terms at all. Maryse Mitchell-Brody of The Icarus Project in New York has described how our feelings can inform us of what’s wrong with the world, rather than what’s wrong with us (what we commonly call “symptoms”). - Louise Tam

Notes on language: "Mad Pride activists seek to reclaim language that has been used against us such as “mad”, “nutter”, “crazy”, “lunatic”, “maniac”, and “psycho”. Reclaiming language is political and challenges discrimination. Mad Pride participants use and refuse a variety of labels. We choose “mad” as an umbrella term." - http://www.torontomadpride.com/what-is-mp/

General Education Resources

- Mad Matters: A Critical Reader in Canadian Mad Studies by Bren A. LeFrançois, Robert Menzies, Geoffrey Reaume

- Mad in Canada

- Fireweed Collective

- Madness & Oppression: Paths to Personal Transformation and Collective Liberation

- Hearing Voices Network

- MindFreedom - Knowledge Base

- The Ex-Patients’ Movement: Where We’ve Been and Where We’re Going

- Mad Feminism

- History of Madness by Michel Foucault

- Mad People of Colour: A Manifesto

- Mad But Not Crazy: On 'Suicide' and the 'Psy' Complex by Louise Tam

Shayda on mental health in academia, creating #AccessIntimacy, & her upcoming book on #SinsInvalid!

Performing Arts Resources

- Disability as a Creative Arts Process by Stephanie Heit (article)

- Smorschok, M. (2021). Magic and madness: An autoethnographic creative nonfiction arts-based research project exploring the makings of Mad Home within and outside of dance spaces.

- Call Me Crazy - script by Paula Caplan

- Foucault, M. (2023). Literature and Madness: Madness in the Baroque Theatre and the Theatre of Artaud. Theory, Culture & Society, 40(1-2), 241-257. https://doi.org/10.1177/02632764211032717

- HowlRound:

- Bruun, E. F., & Steigum, J. B. (2023). The Drama Space as Companion: Students’ Perspectives on Mental Health in Upper Secondary Drama Education. Nordic Journal of Arts, Culture and Health, 4(2), 1-11.

- Mendelowitz, F. R. (2023). Using Applied Theater to Promote Social-Emotional Health in Adolescents. Group, 47(12), 53-66.

- Stephenson, L. (2023). Collective creativity and wellbeing dispositions: Children's perceptions of learning through drama. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 47, 101188.

Re-Threading Madness podcast with JD Derbyshire who is a writer, comedian, mad activist, performer, playwright, theatre maker, director, inclusive educator.

Chad Taylor is a creative dancer and choreographer who has worked with artists such as Sade, Meatloaf and Little Mix. He has experience of depression and psychosis which inspired some of his creative work.

CODE Resources

- Financial Literacy and Making Choices (Addition) – Grade 5 Dance – Public

- Finding Balance – Intermediate Dance/Drama – Public

- Outside and Inside: Mask // Extérieur et intérieur : masque – Intermediate Drama – Members Only

- Heroes – Intermediate Drama – Public

Community Practitioners

- Kevin Edward Turner and the Company Chameleon (UK) - makes dance theatre nationally and internationally. He has bipolar disorder that has required inpatient care.

- Jess Thom and Touretteshero (UK) - artist, playworker and co-founder of Tourretteshero, diagnosed with Tourettes in her twenties.

- Selina Thompson (UK) - an internationally recognised live art and theatre maker, with experience of anxiety and Bipolar II.

- Lemn Sissay (UK) - is a poet, playwright and activist. He lives with the effects of childhood trauma.

- benji reid (UK) - award winning photographic artist, theatre director, and dancer with lived experience of severe depression, anxiety and an addiction disorder.

- Cheryl Martin (UK) - director, theatre maker and co-CEO of Black Gold Arts festival. She has previously made work around her experience of depression and borderline personality disorder.

- Darren Pritchard (UK) - dancer and choreographer living with dyslexia. He is also co-CEO of Black Gold Arts and is Mother of House of Ghetto.

Neuroableism

Neuroableism is:

the specific type of ableism experienced by neurodivergent people due to systemic oppression in a supremacist-based society that values neurotypicalness as the “right” way to be, think, and act.

The term “neuroableism” was coined in 2019 by Julia Feliz. - http://www.neuroableism.com/

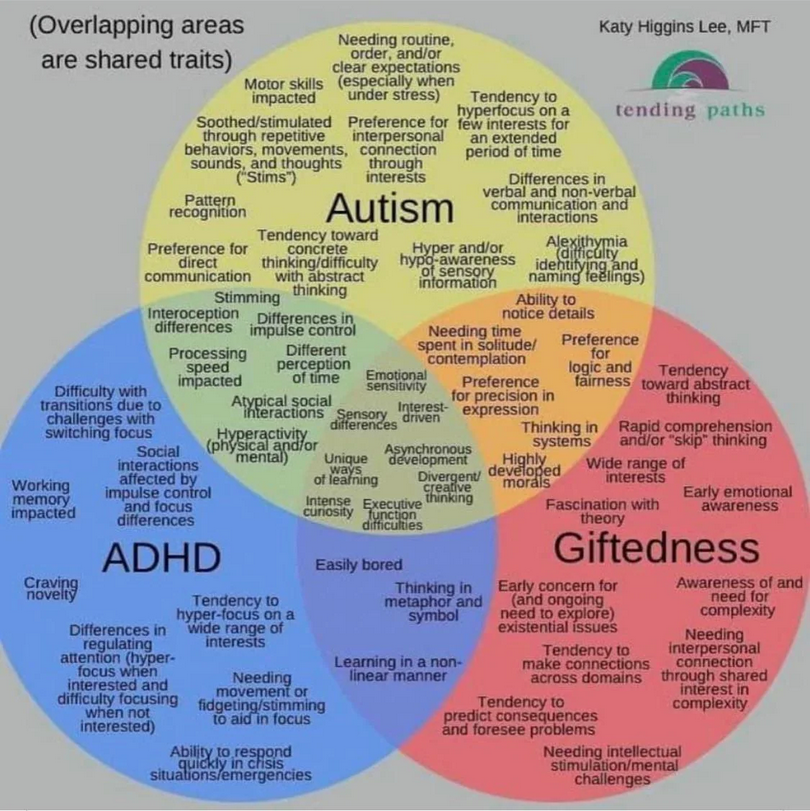

A non-exhaustive list of different types of neurodivergence includes autism, dyslexia, dyscalculia, dyspraxia, ADHD, epilepsy, hyperlexia, OCD, Tourette's. A neurodivergent person can live with multiple forms of neurodivergence and these can exist alongside depression, anxiety, and other forms of madness.

Neuroableism often manifests as the identification and accommodation of neurodiversity as a form of "special needs" in educational spaces, but all human beings have needs and everyone benefits from the availability of multiple ways to access learning and engagement in performing arts.

Neuroableism can manifest on the individual level through stigmas and bias and at institutional structural levels. Examples include lower expectations for folks labeled with "special needs", language related to "functioning" that relates the person's worth to how neurotypically they present (or mask), or in the " processes, procedures, and cultural norms that systemically disadvantage people from sensory sensitive, autistic, dyslexic, ADHD, PTSD, and other neurominority and neurodivergent communities. This form of systemic discrimination includes [...] work organization, and cultural norms that privilege neuronormativity [or neurotypical supremacy]—a socially constructed set of expectations for preferred workstyles, verbal and non-verbal communication and behavior, sensory tolerances, and emotional processing and expression." - https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/positively-different/202309/what-is-structural-neuroableism-at-work

Some neurodivergent people consider themselves to be disabled and some do not. Some choose not to accept labels because of the assumptions about what those labels mean. Some may choose not to identify based on internalized ableism.

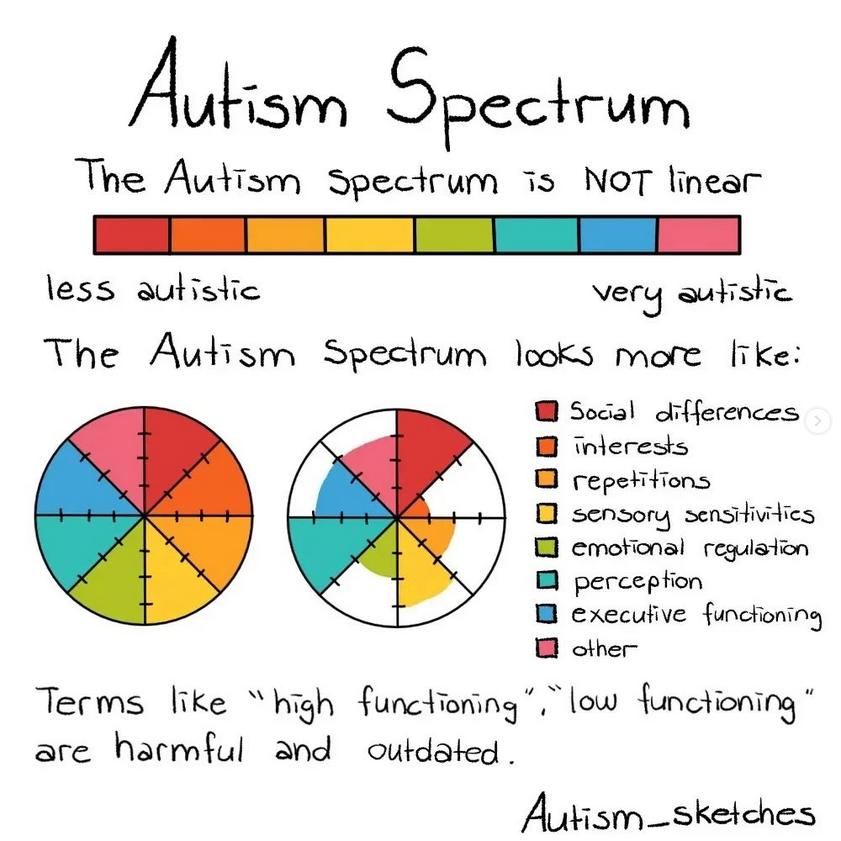

Many forms of neurodivergence exist on a spectrum and do not manifest in uniform ways across individuals that live with them. Consider the Autism Spectrum:

In another slide, Anouk (autism_sketches) recognizes that this is a simplified representation and there may be additional "pieces" to the pie. The overall point is that autism may look different for every Autistic person and that the notion of the spectrum is better applied to access needs than to the concept of autism as a whole.

The measurement of IQ has been used to support eugenics and used to restrict immigration. These tests are often culturally-biased and contribute to racism. IQ tests measure a narrow range of cognitive abilities and are influenced by a variety of factors, including environment and education. While autism and intellectual or developmental disabilities can co-exist, functioning labels often refer to how well an individual masks and how well they approximate neurotypical behaviour. These labels often fail to communicate meaningfully about someone's access needs.

There are many overlaps in these access needs across forms of neurodivergence. Consider this resource which suggests shared and distinct traits among these identities:

How might access needs identified by Anouk (autism_sketches) and by Kathy Higging Lee (Tending Paths) be useful for engaging in Universal Design for Learning or innovating new ways to engage in dance and drama?

General Education Resources

- About Us: Learn more about LD@school - LD@school

- Overview - LD@school

- Walker, N. (2014, September 27). Neurodiversity: Some basic terms & definitions. Neurocosmopolitanism. https://neurocosmopolitanism.com/neurodiversity-some-basic-terms-definitions/

- What is autism?

- The Problem with "Asperger's"

- "Functioning" Labels and Ableism

- Designing spaces for neurodiveristy

- Autism Accessibility resources - Autism Self-Advocacy Network

- Neuroqueer // Neuroqueer: An Introduction // Toward a Neuroqueer Future // Throwing Away the Master's Tools: Liberating ourselves from the pathology paradigm

- Sinclair, J. (2012). Don't Mourn for Us. (Conference on Autism)

- Ari Ne'eman. The Future (and the Past) of Autism Advocacy, Or Why the ASA's Magazine, The Advocate, Wouldn't Publish This Piece.

- Broderick, A. A., & Roscigno, R. (2021). Autism, Inc.: The Autism Industrial Complex. Journal of Disability Studies in Education, 2(1), 77-101.

- Just Stimming

- The neurodiversity movements needs its shoes off, and first up. by Lydia X. Z. Brown (on respectability politics and anger)

Sensory-friendly or Relaxed Performances

Sensory-friendly performances may be essential for some folx accessing theatre experiences, but the existence of sensory-friendly performance options benefits anyone who may have a negative experience with sensory input.

"Sensory-friendly performances are designed to create a performing arts experience that is welcoming to all families with children with autism or with other disabilities that create sensory sensitivities. Accommodations for these performances include:

- Lower sound level, especially for startling or loud sounds;

- Lights remain on at a low level in the theatre during the performance;

- A reduction of strobe lighting or lighting focused on the audience;

- Patrons are free to talk and leave their seats during the performance;

- Designated quiet areas within the theatre;

- Space throughout the theatre for standing and movement; and

- Staff trained to be inviting and accommodating to families' needs."

- The Kennedy Centre

Resources may be provided to patrons in advance to prepare for a theatre visit such as social stories, story synopsis, and a seating map. As an example, Goodman Theatre provides Sensory Bags for all performances: "These bags contain noise-reducing headphones, two fidgets, a notebook and pen, a social story about visiting Goodman Theatre, and a picture communication keyring."

Theatre and Autism: A special place for special needs

- Sensory Theatre: How to Make Interactive, Inclusive, Immersive Theatre for Diverse Audiences by a Founder of Oily Cart by Tim Webb

- Oily Cart: How to Make Interactive, Inclusive, Immersive Theatre for Diverse Audiences

- Establishing Sensory Inclusive Theater Experiences (includes examples of sensory bag materials such as social stories)

- Making Sensory Theatre for All Ages and Senses - includes images from past Oily Cart productions

Performing Arts Resources

- Bur Oak Secondary School breaks down barriers with "Shoes"

- Delaney, T. (2009). 101 Games and Activities for Children With Autism, Asperger’s and Sensory Processing Disorders

- Gold, B. (2021). Neurodivergency and Interdependent Creation: Breaking into Canadian Disability Arts. Studies in Social Justice, 15(2), 209-229. https://journals.library.brocku.ca/index.php/SSJ/article/view/2434

- Magni, S. (2020). Towards a Theatre of Neurodiversity: Virtual Theatre and Disability During a Global Pandemic. http://hdl.handle.net/10315/38370

- Martin, A. (2024). Neurodivergence in Dance Performance: A Thesis. Dance Written, 28. https://digitalcommons.slc.edu/dance_etd/28

- Neurodiversity Project: Dismantling Systemic Ableism in the Dramatic Arts https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=44bwuru9Ns4

- Nowack, M. (2020). Weaving Presences, Unravelling Normal: Affirming Diverse Ways of Being in Dance Pedagogy. https://taju.uniarts.fi/handle/10024/6921

- Schmidt, Y. (2017). Towards a new directional turn? Directors with cognitive disabilities. Research in Drama Education: The Journal of Applied Theatre and Performance, 22(3), 446-459.

- Shaughnessy, R. (2023). Shakespeare, performance and neurodiversity: Bottom's dream. In P. Bickley & J. Stevens (Eds.), Shakespeare, Education and Pedagogy (pp. 116-125). Routledge. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9781003188704-17/shakespeare-performance-neurodiversity-robert-shaughnessy

- Vasquez, A. M., Koro, M., & Beghetto, R. A. (2021). "Chapter 14 Creative Talent as Emergent Event: A Neurodiversity Perspective". In Good Teachers for Tomorrow’s Schools. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004465008_015

CODE Resources

Picture Books for Entry Points

Feedback

We would love for you to add to this resource! If you see something missing, have a suggested resource or want to flag a concern with a resource shared here, please use the Feedback button in the left menu. As a team of volunteers, CODE will do our best to respond to these inquiries and update these resources as often as possible.